Reckoning With 'Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics' A Decade Later

The final Aretha album turns 10.

One of the first things that comes to mind when I discuss Aretha Franklin’s final album, Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics, which was released 10 years ago today, is a conversation I had with my friend Philip shortly after the album was released. He said to me, “I hope this isn’t her last album.” He didn’t mean that in an entirely morbid sense. He was more referring to the waning quality of the project that at times overshadows a record showcasing a music titan having fun in her seventies. I’m going to piss off some Aretha stans, and that just means I’m doing it right. If you can’t see and acknowledge a misstep in an artist you love, you are doing yourself and them a great disservice. I had a tattoo artist etch Aretha’s name onto my ribcage the day she died. If I can acknowledge missteps, you can too.

Reckoning with this album is a continuing and evolving experience. At the forefront, this is the final full-length body of work of Aretha Franklin’s career, bookending more than half a century of releasing music, affecting souls, and influencing generations. And she’s doing one of the things that made her such a tremendous force in music: taking on other people’s songs. While she excelled at singing, songwriting, playing piano, and performing, she was also an interpretive genius. I don’t have an exact count on how many covers Aretha recorded, there are multiple albums where the covers rival, and even outnumber, the original material. In fact, of the nearly 40 studio albums Aretha recorded, there are no more than 4 albums that do not contain at least one cover. And many of those were number one hits and/or Grammy Award winners, among them “Respect,” “I Say A Little Prayer,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “You’re All I Need To Get By,” “Spanish Harlem,” “Don’t Play That Song,” “Ain’t Nothing Like The Real Thing,” “Hold On (I’m Coming),” and “A House Is Not A Home.” There are many others, too, that might not be big hits, but are magnanimous interpretations: among them “Dark End Of The Street,” “You Light Up My Life,” “You Send Me,” “A Change Is Gonna Come,” “Can’t Turn You Loose,” “It’s My Turn,” “Somewhere,” “Skylark,” and “What A Diff’rence A Day Made.”

In tandem, this album is also Aretha having fun with a set of songs that run the gambit. Some of them influenced her when she was young, others competed with her own hits, and some were influenced by her. You can hear it in the vocals, and the playful flourishes and spoken bits that she adds: she had a good time recording these songs. I think that, after 54 years of professionally recording music, she earned the right to have some fun.

However, Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics is also plagued by poor decision-making and execution, which robbed the album of its potential. At times material on this album isn’t befitting of the Queen of Soul. Some of these arrangements of these ‘diva classics’ are, not classic. They often lack the creative zest that made an Aretha cover (like many of the aforementioned songs), unique. Some of them come out sounding like tracks you’d hear at a karaoke bar, and that’s just not the kind of track Aretha Franklin should be singing over.

And let’s get this out of the way early: on every song across this album, Aretha Franklin’s vocals are processed with a pitch correction software (one type is AutoTune, although that may not be the exact software used here). It is applied so poorly that anyone can hear it. Whoever was involved with putting pitch-correction on Aretha Franklin’s vocals and allowing it to remain there should, frankly, be prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law (and then some). Distorting the authenticity of one of the most emphatic and soulful voices of all time with technology is one of the greatest assaults on popular music we will ever witness. Having attended a few shows where Aretha sang these songs live, I can attest to her capacity to deliver them without the need for any vocal enhancements. As a fan, words simply do not express the magnitude of my disgust, disappointment, and sadness with hearing Aretha Franklin’s voice shamelessly processed through pitch-correction technology.

Finally, there were some shake-ups with the tracklist along the way. Songs that were announced as part of the album never materialized, and those omissions detracted from the experience. I still hope those songs will materialize someday, if they were completed. Let’s dive into the history and content of Aretha Franklin’s final album, Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics.

This album marks the reunion of Aretha with Clive Davis, who orchestrated Aretha’s resurgence in the 1980s after signing her to his Arista Records in late 1979. It’s also their first full-length collaboration since 1998’s triumphant A Rose Is Still A Rose. Davis first announced the ‘diva classics’ concept for Aretha’s next album in an interview with Billboard during the lead-up to the 2013 Grammy Awards. He told Billboard that the album would contain, “great diva signature songs and (the public would) hear that voice, that incredible national treasure voice of all time (sing these classics).” The irony is strong considering the pitch-correction that smothered Aretha across the final product.

At the time, Kenny “Babyface” Edmonds and Danger Mouse were attached to the project. Babyface (as Aretha called him) and Aretha had a long working history. They first collaborated on “Willing To Forgive” and “Honey” from Greatest Hits 1980-1994, but also 1995’s tremendous “It Hurts Like Hell,” and 1999’s Mary J. Blige duet “Don’t Waste Your Time,” along with a few other cuts over the years. Danger Mouse had never worked with Aretha. Some might remember his infamous 2004 Jay Z/ Beatles mashup project The Grey Album. Up to 2014 he also demonstrated his tremendous skill on original work, such as his work as half of Gnarls Barkley alongside Cee-Lo Green, a spread of Black Keys LPs, Norah Jones’ Little Broken Hearts, and Gorillaz’ Demon Days.

Unfortunately, Danger Mouse departed the project before it even began, moving on to work on what became U2’s 2014 LP Songs of Innocence (the one that magically appeared uninvited on hundreds of thousands of iPhones). Babyface remained attached to the project as one of the producers, and veteran producer Don Was was soon also attached as another producer. Though both appeared with Aretha during a fall 2013 press conference in Detroit, Was soon detached from the project for unknown reasons. In an op-ed for Billboard after her death, Was described the immensity of standing alongside Franklin while she sang and played at that press conference. Hearing her sing “People” at the piano that day brought him to tears. He developed an unrealized aspiration to produce an LP of just Aretha and the piano, which he made another attempt at not long before her death.

As a fan, it was hard to be anything but ecstatic about the album as these press items circulated. Her previous album, 2011’s Aretha: A Woman Falling Out Of Love, was teased and delayed for more than half a decade, and though it featured moments of brilliance and great singing, it’s not one of the high-value gems in the Queen of Soul’s crown. With Clive back in the driver’s seat, and covers on the roadmap, it seemed like Aretha was going to have another incredible record on her hands.

At least 16 songs were conceptualized and to some degree realized during the creative process of Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics. 10 made the final cut. Three that didn’t make the cut were teased as confirmed inclusions up to 2 months prior to the album’s release. Aretha mentioned another three on one of her personal Facebook profiles. It is unknown whether these 6 outtakes were completed, or even recorded.

The concept was already exciting, but as songs slated for the album were revealed, the album became even more appetizing. Among the songs reportedly recorded were Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got To Do With It,” Donna Summer’s “Last Dance,” and Alicia Keys’ “Fallin’.” It’s unclear whether these songs were recorded or even prepared, but it’s worth noting that those inclusions were reported to the press less than 3 months before the LP came out.

Some tracks were prepared and not used. Aretha had a secret Facebook account or two (one under a pseudonym) where she posted, at times more than she meant to, including about the album while it was in the works. Seeing the posts on her profiles is actually incredibly heartwarming. It humanizes her in a way that her guarded public persona sometimes didn’t allow in interviews. Aretha comes across like your grandma who doesn’t fully understand how social media works (which also aligns with stories told by people she kept in touch with including Michael Eric Dyson and Don Cheadle). She posted things she must’ve thought she was sending as a text message or as a private message just to one person. Her posts are full of disjointed words, typos, and that express confusion and frustration with social media (a relatable experience for all).

In March 2014, she posted a status update that the new tracks were coming in and she loved them. Around that same time, on the same Facebook profile, she replied to a journalist friend’s wall post that 6 tracks were ready: “Rolling In The Deep,” “At Last,” a Dinah Washington track, and two songs that never materialized: “That’s All I Want From You” (which she first covered on 1970’s Spirit In The Dark), and Vicki Carr’s “It Must Be Him.” She also apparently “found” the track for “Greatest Love of All” but was unsure if it was being recorded.

Though she shared those things on social media, and teased the album in the press, in concert she was cagey about presenting the material prior to the album’s release. Save for one late night premiere performance, she didn’t perform any of the new songs until after the album was released.

What dismays me most about this record is that it feels like everyone dropped the ball. Clive didn’t run the show like the tight ship he had in the past. Babyface certainly didn’t bring his best to the table. And Aretha. Aretha recorded these arrangements that are not on par with her extensive history of reimagining songs she covered. And more than anything else: no one put a stop to the rampant pitch correction on Aretha’s vocals.

An Aretha cover was special because of what Aretha made it. Along with her collaborators, she had the ability to hear things we couldn’t, to feel things we either didn’t know were there, or that could be there, and to subsequently shake us to our core with those feelings she elicited. Aretha Franklin was an artist who saw the statue lying beneath a block of marble or the carving within a gorgeous oak tree, clamoring to be released. Her canvases weren’t always bland, jagged, or unfortunate; some were gorgeous. But even in those gorgeous canvases Aretha often saw beauties we didn’t realize were there, and she drew them out naturally, as if she were a magnet.

What this album lacks in large is both that touch and that pull. Her musical instincts don’t seem to be in the driver’s seat on most of these arrangements; she’s but a passenger, despite co-production credit on three cuts (“Rolling In The Deep,” “Midnight Train To Georgia,” “I Will Survive”). The direction they take is largely not befitting of her magnitude. And that’s not a new experience either. The Washington Post said that her previous album, Aretha: A Woman Falling Out Of Love “appears to indulge every wrong musical instinct Franklin has ever had.” Harsh as that was, some of the songs on that album certainly lived up to it.

Aretha’s voice is the centerpiece of every Aretha recording. It’s hard to divorce myself from my very insulated position as a rabid, constant listener to Aretha’s music, to truly sense how detrimental the pitch correction is to this album. It certainly disrupts my experience, but I’ve come to enjoy these recordings for what they are, while making space for the frustration that still recurs when listening.

For those who aren’t aware, pitch correction software essentially smoothes out the rough edges on a vocal and fixes off-key imperfections. Unless you’re going for a sound like Cher’s “Believe” or T-Pain in his heyday, pitch-correction software is supposed to be applied with a precision and subtlety to go undetected. That’s not the case here. It’s done so poorly that it’s blatant, and subsequently distracts from everything else happening. At its best, the pitch correction is distracting; at its worst, it’s dismantling. And while the great voices of later generations have also used it (you can hear it on Whitney Houston’s final LP, 2009’s I Look To You, Kelly Clarkson’s 2023 LP chemistry and on Mariah Carey’s stellar contributions to Ariana Grande’s 2024 hit “yes, and?”), that doesn’t mean any of these great, soulful voices should.

To understand what we lose with pitch correction software, look no further than Aretha herself and her signature song. When Aretha recorded “Respect” on Valentine’s Day in 1967, she had a cold. You can actually hear her voice crack on the end of “what you need.” If pitch-correction existed then and was used, it would have erased that moment, which certainly doesn’t detract from what’s been called the greatest song of all time by Rolling Stone.

Using pitch-correction on Aretha’s instrument, which was once declared a natural resource by the state of Michigan (and to do so with such amateur execution that even a casual listener can hear it) is one of the most egregious actions ever taken in the history of recorded music.

Babyface ended up handling half the album’s production, with assistance from Antonio Dixon and Dapo Torimiro on certain tracks. To fill in the gaps, Aretha was adorned with some of the best in the business: Terry Hunter, Eric Kupper, and a rare but thrilling production appearance from Outkast’s Andre 3000. Harvey Mason Jr., who is now the president of the Recording Academy, handled vocal production on two cuts. Clive Davis and Aretha oversaw the project, engaging in their usual exchange of ideas and songs to decide which they’d tackle, and also earned a few production credits.

Though some of the tracks are almost entirely programmed, or the instruments performed by producers such as Babyface and Dixon, there are a few notable musicians who accompanied Aretha on this record. Both Big Jim Wright and Greg Phillinganes can be heard on the keys, and Kirk Whalum delivers the saxophone solo on “At Last.”

A serious crew of background singers was also behind Aretha for much of this album, led by Fonzi Thornton, and also including Brenda White-King, Tawatha Agee, and Vaneese Thomas. Thornton and King first backed Aretha up on her two Luther Vandross-produced LPs in the early 1980’s. Most significantly, and unbeknownst to many who like to joke about “that” performance, Cissy Houston was also featured as a background vocalist on more than half the album. It marked her first appearance on an Aretha album in over three decades, since those early 80’s Vandross-produced LPs.

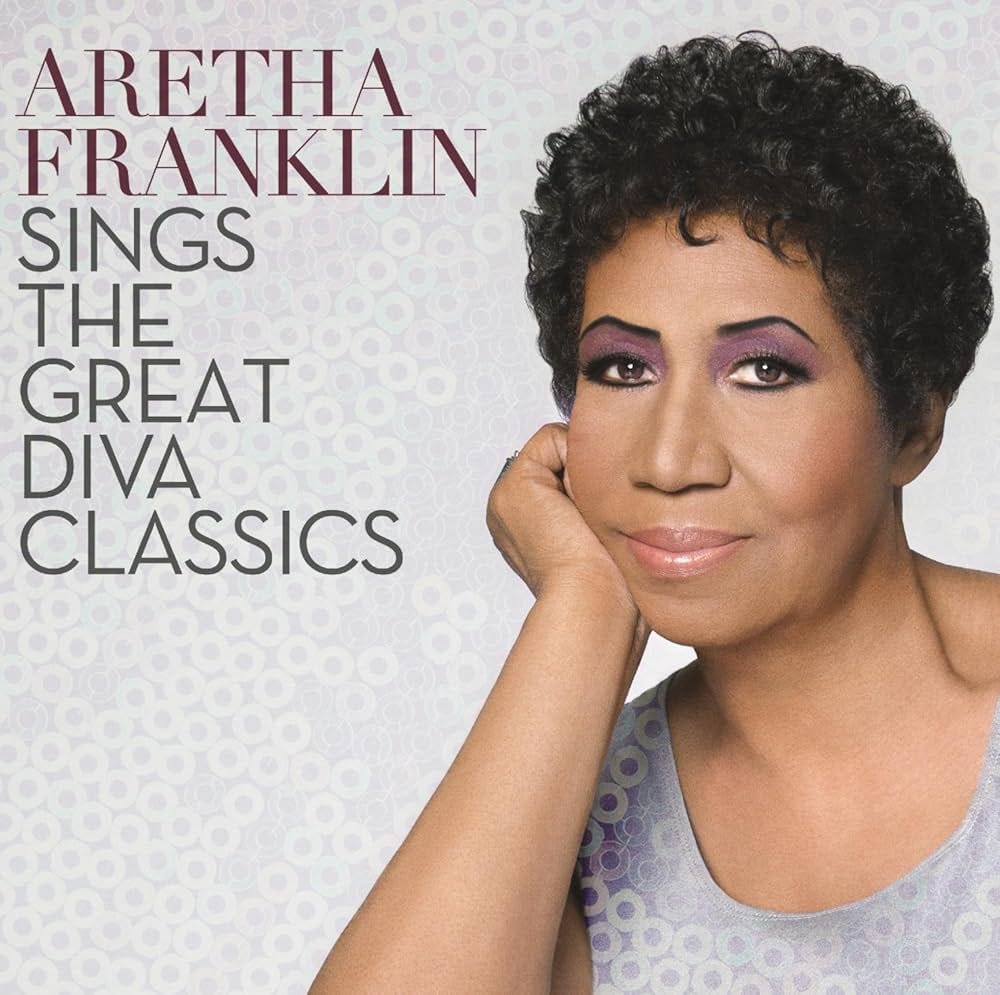

For the artwork, Aretha turned again to Matthew Jordan Smith, who had been photographing her for the better part of the last decade. Smith also photographed Aretha for her previous LP, 2011’s Aretha: A Woman Falling Out Of Love. He released a book this year chronicling his work with her called Aretha Cool, which even features some outtakes from this shoot.

Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics opens with one of the most faithful readings of the album, “At Last,” which was immortalized nearly 20 years after being first released, thanks to Etta James’ unparalleled 1960 recording. This isn’t Aretha’s first rodeo with the song: she first recorded a different arrangement during the 1973 sessions for Let Me In Your Life (which didn’t see the life of day until 2007’s Rare & Unreleased Recordings from the Golden Reign of the Queen of Soul). She also performed it alongside Lou Rawls in 2002.

This 2014 recording emphasizes saxophone and incorporates a hard bass drum instead of the still-present strings, which gives it a jazzier center of gravity. Vocally her choices are fine, but it really becomes an Aretha cover during her live performance on the Today Show. That performance surpasses this studio version. She sings to the track, and her upper range sounds limited until the very end, but her melodic brilliance is the ultimate gratification.

Similar is her take on Barbara Streisand’s “People,” which she first recorded 50 years earlier in 1964. There’s something stunning about putting these two recordings side-by-side. She’s just 22 years old in the first recording, and though she demonstrates her power, she’s singing it fairly straight. But on this 2014 recording, she’s in full control. Again, pitch-correction detracts, but her vocal is nonetheless affecting. The wisdom and experience of the last half-century are palpable.

Aretha also uses her impeccable ear to devise twists on two songs to elevate them and help her further stake her claim to each. One of her producers had a third twist in mind that served as a wonderful tie-inn to her own diva classic.

Aretha’s first twist came on the lead single “Rolling In The Deep” which is adorned with ‘The Aretha Version’ in parenthesis, a hint that there’s a twist. That twist comes at the end of the bridge, when Aretha veers into the Motown classic “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough.” The songs marry magnificently. She knocks this one clear out of the park, and though the pitch-correction is at its worst here, it doesn’t entirely disembowel this moment. She debuted the song in late September 2014 on the Late Show with David Letterman. I go in depth on “Rolling In The Deep (The Aretha Version)” here.

The vocal effects also distract and detract from the arrangement of “I Will Survive,” particularly at when her voice is more prominent during the introduction and first minute when it progresses into a deconstructed dubstep beat. Terry Hunter, alongside DJ Wayne Williams and Aretha herself, crafted a solid arrangement to this Gloria Gaynor disco classic. Nothing beats the reaction of a first-time listener when the disco beat evaporates and is replaced by booming bass and trap hi-hats readjust as Aretha pivots into the hook of Destiny’s Child’s “Survivor.”

Though the convergence of these two resilient records seems to have originated on a 2012 episode of the TV series Glee, Aretha claims credit for the idea. And based on the blend present here, where “Survivor” operates differently than it did on “Glee,” it seems plausible that Aretha wasn’t keyed into the happenings on the series. It’s a wild and surreal moment, but a brilliant marriage of two classics.

Post-breakdown, Aretha starts really having fun. She adjusts and speaks the next part of “I Will Survive,” most notably injecting a heavy dose of sass into the now-spoken, “so you felt like stopping by and expected me to be free?” before replacing the classic “go, walk out the door,” with a firm “beat it! Get to stepping! Keep it moving!” Even her “heh-heh-ha-ha” has a playfulness. So does her, “this is me. Sho’ ‘Nuff Ree!” You can tell she had a good time in the studio adding these embellishments, and arranging background vocals that support many of them.

Eric Kupper, who has become a stalwart producer, especially in the remix arena (see his 2020 remix of Gaynor’s “I Will Survive” and his 2020 Diana Ross remix LP Supertonic), gives Aretha a solid dance arrangement of Whitney Houston’s Narada Michael Walden/C&C Music Factory reinvigoration of Chaka Khan’s Ashford and Simpson classic “I’m Every Woman.” This arrangement wouldn’t be out of place as a remix beneath either Chaka or Whitney’s vocals. His emphasis on the bass drum and keyboards serves Aretha well.

But Kupper really earned his keep with the twist he devised for “I’m Every Woman,” which serves as a great companion to Aretha’s blends on “Rolling In The Deep” and “I Will Survive.” Just when you think Aretha is about to go into the song’s iconic bridge of “I ain’t braggin,” the “I” instead bends into an “r” and she’s spelling out her word: “R-E-S-P-E-C-T.” Kupper segues the record into her classic. Hearing her sing it, more than 45 years later, over a dance beat, seems perfect. It’s also a nice little reminder, for anyone that forgot, Aretha Franklin is the diva classic.

She said “whoa!” when she heard “Respect” incorporated into the track, she later told David Nathan during an interview about the album. Audiences loved it too. “I’m Every Woman/Respect” was one of the recordings she previewed during an interview at the 92nd St Y in New York City, the audience roared with excitement when she veered into “Respect”, and erupted again when she didn’t just sing that iconic bridge, but also delivered the first verse.

Aretha brought “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough,” and “Survivor” as twists, but she also brought “Teach Me Tonight,” which was made a hit by one of Aretha’s idols, Dinah Washington. “Dinah Washington could sing. Period,” Aretha told David Nathan in 2014. Aretha revered Dinah such that, when Dinah unexpectedly passed away in late 1963, she recorded an entire album to remember her; Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington.

“It was one of her more popular things that I liked,” Aretha told David Nathan about selecting “Teach Me Tonight,” one of the strongest moments of the album. It’s a shame she didn’t accompany herself on piano, but she still sounds damned good in front of this piano-centric jazz arrangement. That piano emphasis grants the song a slightly new edge, while feeling just right for Aretha. Again, overdone pitch correction meddles with greatness, but her vocal choices of melodic embellishment and timing are hair-raising on a song that has been proven to be a playground not just for Washington, but a who’s who of greatness from Ella, Sarah, and Sinatra, to more contemporary readings by Etta, Chaka, and even Amy.

Her cover of the Motown classic “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” by The Supremes is, like “At Last” and “People,” her second stab and radically different from her first, which was recorded in 1969 during sessions for This Girl’s In Love With You and Spirit In The Dark, but also not released until 2007 on Rare & Unreleased alongside “At Last.” The 1969 version was a modest, meandering but punchy moment that hinged on the agony of hanging on.

Here, Aretha once again assumes the role of dance queen over a classic Terry Hunter production. The arrangement is fresh, well done, and well-suited to the song. What makes it really special is that Aretha accompanies herself on piano. It remains the final recording to be released featuring Aretha at the piano (though there’s surely a few other things in the vault recorded after this). You really get to hear Aretha on the keys when most of the arrangement drops out near the song’s end and the horns mimic the chords. It’s not a complex part, but it’s always a thrill to hear Aretha at the piano.

Covering Alicia Keys, like Adele, seemed like a no-brainer. Aretha had not only sung with Alicia in 2003 at Clive Davis’ Pre-Grammy party, she’d also covered both “No One” and “You Don’t Know My Name” in concert over the years. Initial reports about the album named “Fallin’” as the Alicia cut Aretha recorded. Imagine for a moment: Aretha giving a gritty, bare bones reading of “Fallin’” (which, like “Rolling In The Deep” is bursting with Aretha’s DNA), featuring just Aretha at the piano with some well-placed strings. It would have been tremendous.

Unfortunately, that’s not what made the album. Instead, Aretha covered “No One” and gave the song a reggae twist. Keys herself suggested the reggae direction for the song to Davis during a lunch the two had together. It sounds exciting and inventive, unless you remember that Alicia released a reggae mix of “No One” by Curtis Lynch alongside the original back in 2007. Aretha’s version, produced by The Underdogs, seems to rely quite heavily on the remix, robbing it of its originality and inventiveness.

The worst cover though, comes early, in the form of “Midnight Train To Georgia,” originally performed by Cissy Houston but made famous by Gladys Knight and the Pips. Houston’s original was very “Home On The Range,” with a soulful elevation thanks to Houston’s incredible voice. Knight’s definitive version is pure R&B. Aretha’s version isn’t challenging the quality of the original or the definitive take.

The problem with Aretha’s version is that the different elements of the arrangement come together terribly. The percussive introduction sounds like workers on a railroad, which is fitting, until it combines with and then yields to a poorly produced mix that ends up sounding like a soulless karaoke backing track. Even the background vocals are bad, which sound pitched-up and technologically modified, rendering contributions from Cissy Houston herself, and Aretha’s reliable and fantastic background vocalists Fonzi Thornton, Tawatha Agee, Latrelle Simmons, Brenda White-King, unrecognizable. The pitch correction is also in full effect on Aretha’s lead vocal, making for an all-around ghastly affair. The one redeeming moment is near the end when Aretha riffs off of “on the mid.”

Aretha performed it just once at NJPAC in Newark in March 2015. Her band rested their instruments and looked on while she sang to the awful track. Yours truly captured the performance, which, despite highlighting the terrible arrangement, does excel thanks to Aretha’s stellar live vocal performance. The background singers also add a little extra flair as the song continues.

Andre 3000, best known for being half of the immense duo OutKast, is owed the biggest debt of gratitude for his contribution to this LP. His work is the biggest departure from an original on this album, making it the most Aretha-true cover on the LP.

“Nothing Compares 2 U,” the Prince-penned record that Sinead O’Connor rocketed to classic status is completely unrecognizable after 3-Stacks and Aretha are through with it. Gone is the gut-wrenching ballad and in its place is cool, upbeat, and breezy jazz record. This is the sort of cover that defines Aretha Franklin. It renders the song entirely unrecognizable, while putting Aretha back in one of her favorite arenas: jazz. She even comfortably scats her way through the instrumental breakdown. It’s always a thrill to hear Aretha scat. This arrangement closing out the album feels like a magnificent way to bookend her professional recording career, which opened with a peppy jazz number called “Won’t Be Long” on her 1961 Columbia Records debut album.

Commercially, the album had modest impact. It debuted in the top 20 of the Billboard 200. “Rolling In The Deep” made it to number 1 on the dance chart, and became her record-setting 100th entry on the R&B chart. It received no nominations, awards, or certifications otherwise.

As Bob Lefsetz critiqued, “At Last” is still Etta’s, “People” still Barbara’s, and so on. But perhaps he encapsulated it best: “when I let my guard down, I catch myself chuckling over how she floats and rocks and skirls and squalls through each of them.”

Other reviews ran the gambit. Entertainment Weekly gave the album a B- while calling most of it “dated or ill-conceived,” comparing it to a soundtrack to Gay Pride 1977. Rolling Stone awarded it 3.5 stars and called it “delightful.” AllMusic complimented the energy, enthusiasm, and fun she clearly had recording the album, but made note of the “vocal shortcomings and audible use of Auto-Tune.”

Maybe Aretha had too much fun on this one. And maybe that’s okay. Didn’t she give us enough of herself over the years to earn this? Maybe. But everything else aside she certainly didn’t do all that work to earn amateur, sloppy pitch correction on her tremendous instrument.

I’d still like to know what happened to songs that were initially announced as part of the set, including Tina Turner’s “What’s Love Got To Do With It,” Donna Summer’s “Last Dance,” and Alicia Keys’ “Fallin’.” Imagine Aretha tackling any of those. The thought is thrilling, and this 10th anniversary would have been a perfect opportunity to liberate those cuts. There is again also a chance that they were never completed or the arrangements were deemed subpar, which says something based on what was deemed acceptable.

Like Aretha Franklin, Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics is not one dimensional. It’s not simply good or bad, neither brilliant nor thoughtless, neither tight nor sloppy. It’s everything. There’s moments of pure genius, and moments that are just a mess. It’s certainly not the triumph it set out to be, but it’s also not absent from moments that highlight the singular greatness of the Queen of Soul.

A remix LP was subsequently released a few months later, featuring half a dozen mixes of “Rolling In The Deep” and extended mixes of Hunter and Kupper’s contributions.