Aretha Franklin's 'Who's Zoomin' Who?' Turns 40

As the 80’s trudged onward, Aretha Franklin reassembled herself back into a commercial juggernaut in the music industry.

The mid-late 1980’s were the era where Aretha Franklin’s career began to momentarily resemble the commercial success she achieved from 1967 through around 1974. With each album released on Clive Davis’ Arista Records, she got a little closer to where she wanted to be: back on top. Her fifth Arista release, 1985’s Who’s Zoomin’ Who? is the most important album she released in the 80’s. It united her with Narada Michael Walden, and resulted in a sonic rebirth that put her back on the cutting edge of pop music.

It was not her first musical rebirth, and far from her last. But it stands as one of the most significant, second only to 1967’s I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You. The work Aretha did at Arista during the first half of the 1980’s built the momentum, in glorious fashion, to reach this moment. She kicked off her tenure with the label in 1980, appearing in The Blues Brothers and delivering a sizzling rearrangement of 1968’s classic “Think.” Her 1981 electric cover of Sam and Dave’s seminal “Hold On, I’m Comin’” earned Aretha her first Grammy Award in over half a decade. Jump To It paired Aretha with Luther Vandross in 1982, during the height of his own success as a solo act. Their musical union became not just Aretha’s first gold-certified album in a decade, but also her first #1 on the R&B chart in 5 years. And then came Narada Michael Walden.

Narada was a different caliber of collaborator, because even though he’d achieved success and been building himself up, his big break was still on the horizon. He’d reach that break in-part thanks to Aretha, and at the same time, a burgeoning Whitney Houston.

He was already on Clive’s radar thanks to the work he’d done on Arista albums by Angela Bofill and Phyllis Hyman. Listening to those tracks, especially the upbeat ones on Phyllis’ Goddess of Love, they possess some of that same percussive flair that becomes focal to his work with Aretha, and others that follow.

It’s not unlikely that Aretha heard those tracks too, since she was always aware of what was happening in music. In her 1999 autobiography, Aretha: From These Roots, she pointed to an album Narada had produced just months earlier in 1984 as her “a-ha!” moment with his work: Stacy Lattisaw and Johnny Gill’s Perfect Combination. There too, you can hear his drummer’s sensibility informing his production and composition, which would fuel his work with Aretha, and later Whitney.

By the time Aretha got into the studio in late 1984, she was ready to get back to work. She embarked on Who’s Zoomin Who? after her longest break since the inception of her professional recording career. She’d recorded or at least released a new album every year for the last 24 years, when she first stepped into a recording studio in August 1960.

A perfect storm of circumstances caused Aretha to more or less take the year off. First and foremost, she engaged in something of a contract dispute with Arista. It turned out to be a misunderstanding, but took some time to sort out nonetheless. Second, a bad flight from Atlanta on a tiny prop plane during the second half of 1983 permanently grounded Aretha. She never flew again, and simultaneously developed acrophobia (a fear of heights).

Third, her father, the revered Rev. C.L. Franklin, passed away in July 1984, after laying in a coma for half a decade. It had been a grueling couple of years, which all started when he suffered gunshot wounds from a home invasion gone bad. This tragic series of events led Aretha to move back to Detroit, where she lived for the rest of her life. Fourth and finally, her marriage to actor Glynn Turman came to an end; their divorce finalized in early 1984.

She may have been away from the studio, but Aretha had been listening to what was popular, as she often did, and had a sense of what was hitting with the pop market. In a 1985 interview with David Nathan (whose praises I need to sing for a moment, because he just brought this interview into the digital era for the first time a week ago), Aretha shares her desire to shoot for a “younger” sound for Who’s Zoomin’ Who? “I like a bop too!” she exclaimed to him.

She cited the Eurythmics’ “Sweet Dreams,” Jon Waite’s “Missing You,” Van Halen’s “Jump,” and recent work by The Rolling Stones, Tina Turner (whose career-defining Private Dancer had been released the previous year, and who would coincidentally cover Waite’s “Missing You” in the 90’s), Lionel Ritche, and “The Night I Fell In Love,” by Luther Vandross, who had produced her last two albums, as the sounds that were resonating with her as she prepared to get back to recording.

Narada and Aretha turned out to be a musical match made in heaven, but Clive Davis originally envisioned Dionne Warwick as Narada’s next musical pairing, not Aretha. After the two met and proved to be a fruitless coupling, Clive suggested Narada give Aretha a call. He jumped to it, if you will, and along they zoomed.

The two hit it off immediately, and through their early conversations, the album’s title track was born. The title track and subsequent album title came from Aretha’s own vernacular. Narada wanted to get a sense of who Aretha was and how she moved through the world before he started writing songs for her. She told him that when she goes out, it’s a ‘who’s zoomin’ who?’ situation, a term she said entered her vernacular up in the early 1970’s when she was in a relationship with Ken Cunningham. Narada never heard the phrase before, and just like “sock it to me” before it, it became a fixture in mainstream vernacular.

“Who’s Zoomin’ Who?” has a sweet, synthy opening full of Aretha riffs, that cuts left into a driving beat bolstered by simultaneous piano and bass synths keyboard. Aretha is in her element, clearly carrying the upper hand as she zooms him and informs the masses of the album’s key word. Key changes take her to further heights as she, the fish, jumps off the hook and asserts herself with some sizzling ad libs.

Walden initially assembled “Zoomin’” and another track, “Until You Say You Love Me” at his studio in San Francisco, backed by an army of talent, and brought the tracks to Detroit for Aretha to record. This trip ushered in the new method of recording Aretha not just for Narada, but for most who followed, now that she was re-rooted in Detroit and grounded from air travel.

Perhaps the least-discussed record on the album is that second track from the initial session. Narada’s still-favorite from the album, “Until You Say You Love Me” is topically something like a vulnerable maturation of 1974’s unrelenting “Until You Come Back To Me (That’s What I’m Gonna Do).” Aretha assumes one of the most despairing roles she ever has in song. She’s not rapping on doors, or tapping on window panes. Instead, she’s languishing and consumed with tears, yearning for him to return and say he loves her.

The music was inspired by “The Beautiful Ones” by Prince, and the soundtrack to Purple Rain, which had been dominating popular music since its release the prior year. He considered Prince to be cutting edge at the time. It seemed logical to him to put Aretha and her gospel sensibilities over an arrangement in that vein. The result? Another beautiful one.

Those two tracks went over so well with Aretha and Clive, that soon Narada was producing most of the album. He’d go back to San Francisco to compose and assemble more songs, and then bring them back to Detroit to cut the vocals with Aretha. Special creedence must be given to the aforementioned Preston Glass, who suggested he make some lyrical adjustments to, and offer Aretha “Freeway Of Love.”

Narada didn’t forge this sound alone, which he’d been inching towards in the previous years. He came equipped with an army of musicians who only further enhanced and expanded Aretha’s sonic profile. Special credence must also be given to Narada’s two songwriting collaborators. First is Preston Glass, who not only co-wrote the initial two songs and added both backgrounds and keyboards through the album, but also suggested that Narada adjust and offer Aretha a song he’d been saving for his own album, titled “Freeway Of Love.” “Freeway” was co-written with Jeffrey Cohen, who co-wrote the rest of what Narada contributed as a composer.

A foundational component to this album is the percussion, thanks in part to Narada being a drummer. He’s not the only percussionist on Who’s Zoomin’ Who? but it’s both his contributions as a drummer and percussionist’s mind applied to these compositions that help to carve out this sound as his own. It’s percussion-centric and from a percussionist’s mind.

He also enlisted the rhythm section from Santana to fill things out even more. Walter Afanasieff, who would become known best for his work in the 90’s, first as Mariah Carey’s main co-writer and co-producer, and later producing for Celine (including “My Heart Will Go On”) and Streisand (who he is still producing today) among others, handles keyboards. Randy Jackson, who many know best for American Idol, but at that time had been a member of Journey, masterfully dominates the synth bass.

On background vocals, it was a who’s who, starting with Aretha’s sister Carolyn, who helped craft the timeless version of “Respect” that we all know and love, and also wrote some of Aretha’s biggest hits. It’s one of Carolyn’s final appearances on record before her death from cancer just three years later.

The Weather Girls’ Martha Wash is also back there for “Freeway Of Love,” as is the one and only Sylvester, on more than half the album. It’s so important to highlight these two names, who were both reaching their own heights around this time, and both were heavily inspired by Aretha. Sylvester was over the moon to be part of this project; it was a lifelong dream for him, even though he wasn’t in the studio with Aretha for the recording. The same goes for Jeanie Tracy (who brought Sylvester to the sessions), Vicki Randle, and Jim Gilstrap.

There are also three musical guests who contribute solos that heighten the album’s musicality. The best known contribution, of course, is Clarence Clemons of The E Street Band, who delivers one of the most blistering sax solos on an Aretha record in years on “Freeway of Love.” Carlos Santana adds some guitaristic flair to Aretha’s duet with Peter Wolf, “Push.” The one and only Dizzy Gillespie drops a brief, yet mind-boggling trumpet solo on the album’s closing cut, “Integrity.” Aretha is a rare breed and caliber of artist who can bring these ranging talents together on one album.

This music suits Aretha in this moment particularly well thanks to the evolution of her voice. By 1984, when recording first took place, Aretha had been singing professionally for nearly a quarter of a century. She’d also been smoking for most of those years, famously, Kool cigarettes. Those years of chain-smoking were beginning to make their mark on the clarity of her tremendous voice. Her instrument is beginning to assume a rasp that would go hand-in-hand with her range diminishing, which is in its early stages here. But she’s still seemingly unfettered by the evolution of her vocal chords.

But that transformation adds an edginess to her voice, which is a brilliant addition to this rock-centric rebirth. It feels right. Maybe in-part because that aligns her with Tina, whose voice always possessed a rough edge.

From the first booming strikes of percussion at the beginning “Freeway of Love,” which wasn’t just the first single, but also the album opener, it was apparent that Aretha was getting into something new. That percussion is deep, heavy, and all-encompassing; a serious component that was necessary and focal to this new sound.

The saxophone stylings of Clarence Clemons, who was making waves in Bruce Springsteen’s E-Street Band, electrify the introduction as the record at once thrusts Aretha ahead and reaches backwards. Narada has said he crafted it using Motown’s Detroit-centric R&B/pop sound inspiration. While Aretha was never a Motown artist, Narada’s inspiration and Clarence’s contribution recall moments when luminaries like saxophonist King Curtis elevated her late 60’s/early 70’s material with their own brilliant touches. And whether intentionally or not, a song about a driving, cut by an artist from the Motor City is a perfect pairing.

It also ushered Aretha into the music video era, marking her very first music video. Shot in Detroit, Narada and Clarence both appear in the video, alongside a host of extras and dancers, and, when the black-and-white video finally reaches Oz and goes color, a pink Cadillac with the license plate “RESPECT.” Fun fact, the Cadillac belonged to the late Jayne Mansfield, and Aretha recalled finding her then-husband Mickey Hargitay’s name written all over the glove compartment.

“Freeway of Love” is a pop confection at its finest, and exactly what Aretha needed at that moment. It’s fun, flirty, irresistibly catchy, and gives Aretha all the room she needs to declare her continuing vocal dominance. She even adds in yet another trademark spoken piece in the middle, all freestyled, according to Narada. And as Narada crafted “Freeway” for Aretha, Clive Davis added another song to his docket for a new, upcoming artist, which he put together during that same session.

If you didn’t know where this was going, consider the sonic profile of Whitney Houston’s “How Will I Know.” It’s lighter than “Freeway,” but it’s got a similar sound and groove, and even intro into the pre-verse, to “Who’s Zoomin’ Who?” After Narada put “Freeway of Love” together for Aretha, he took “How Will I Know,” which Janet Jackson had rejected, and gave it the makeover that would help rocket Whitney to the top of the charts. The songs, like that meme says, were sisters.

“How Will I Know” was released the Whitney’s debut in February 1985, but didn’t get the single treatment until the end of November 1985, almost 6 months after “Freeway of Love” became a summer smash and zoomed to the top of the Black Singles chart, Dance Club chart, and peaked at number 3 on the Billboard Hot 100. You could even say that “Freeway” helped prime the world for the sound that Whitney rocketed to the Hot 100’s summit, twice. It also helped bring Aretha back to #1 for the first and only time since “Respect” on her smash duet with George Michael, “I Knew You Were Waiting (For Me)” from her next record, 1986’s Aretha.

One of my personal favorites on the album is also perhaps the most curious sequentially. Of the album’s first half, Four of five tracks were released as singles, and are upbeat and stylistically akin contemporary records with flecks of pop, rock, new wave, funk, and R&B peppered throughout. The fifth, sequenced as the album’s third track is, from afar, a puzzling inclusion.

“Sweet Bitter Love” was written by the late Van McCoy, who is perhaps best known for “The Hustle,” and known in the Aretha-verse for producing much of her maligned 1979 disco-but-it’s-actually-not album La Diva. It’s a song some had already heard Aretha sing. She first recorded “Sweet Bitter Love” 20 years earlier in July 1964 during her tenure at Columbia Records.

Two years later she recorded it again, in late 1966, as part of a demo tape for Jerry Wexler. It was presented as a sample of material she might record with him as she migrated from Columbia to Atlantic Records.

I cannot suggest enough to go listen to both the 1964 recording and 1966 demo. And later, for the extra-dedicated, dredge up every live performance of it you can on YouTube, specifically from her final years. Her performances of this song are among her best, ever.

What makes this 1985 recording of “Sweet Bitter Love” special is threefold. First, it’s one of three known recordings she made of this song. Second, it’s an Aretha production. And third, it’s the final of the studio recordings of this song, so it’s the most informed on the subject.

It can’t be overstated that Aretha LOVED “Sweet Bitter Love”; she made it a part of her live repertoire, all the way up to some of her final performances. It’s one of the two songs on Who’s Zoomin’ Who? that Aretha produced herself. In true Aretha fashion, she opens the track with nearly a minute of spoken introduction to “Sweet Bitter Love,” underscored by some well-placed vocal melisma, and proceeds to deliver a very different rendition than 20 years earlier.

Listening to Aretha sing this song in 1985, it’s hard not to consider what more she knows now than she did in 1964, at just 22 years old. She was cognizant of that evolution too. “When I sang it as a youngster, I knew it was beautiful,” she said in her autobiography. “But singing it as a mature woman, I more deeply understood and appreciated the lyric.” Her experiences with love, and loss were much more vast, and it’s evident in how she sings this. The fragments of her broken heart shine like a slow-spinning disco ball, reflecting back all the pain in beautiful fashion.

She embodies sweet bitter love with graceful magnificence. And the way she delivers a “my-my-my” run one can’t help but recall a run on the same word on 1972’s “Mary Don’t You Weep” that, though different, is similarly affecting. It’s a reminder: the gospel is always in the pop with Aretha.

On the album’s second track and fourth single, “Another Night,” Aretha finds her strength and resilience in the face of heartbreak. The driving beat, broken chord bassline, and glittering synthesizers make for a positively 80’s moment. It’s the only Narada production that he didn’t compose, and was written by Italian composer Beppe Cantarelli (Brenda K. Starr’s “I Still Believe,”) and Roy Freeland.

The music video, her third, is her first video with a plot. In it, she’s depicted as a club performer who’s persevering after a breakup with her partner both on and off stage. During this evening, the old partner shows up in the crowd with a new woman, much to the surprise of Aretha’s background singers, whose reactions are nothing short of incredible. Increasingly, he suspects she’s singing about him, until it all culminates in her catching him off-guard mid performance during “my man, I don’t need you to be bringing me down.”

Elsewhere, she’s unconcerned with love and focused on empowerment. Now there was a time, when they used to say, that the idea of Aretha Franklin and Annie Lennox singing together seemed unbelievable. It is still a little wild that this collaboration even happened. Both members of the Eurythmics, David Stewart and Annie Lennox, were surprised when the opportunity presented itself.

Depending on whose version of the story you choose to believe, “Sisters Are Doin’ It For Themselves” was either written for Aretha or Tina Turner. It was a perfect fit for either of them, and Aretha saw it as her first direct declaration of women’s liberation. Yes, songs she sang became emblematic of the movement, but this was the first one created with the movement in mind.

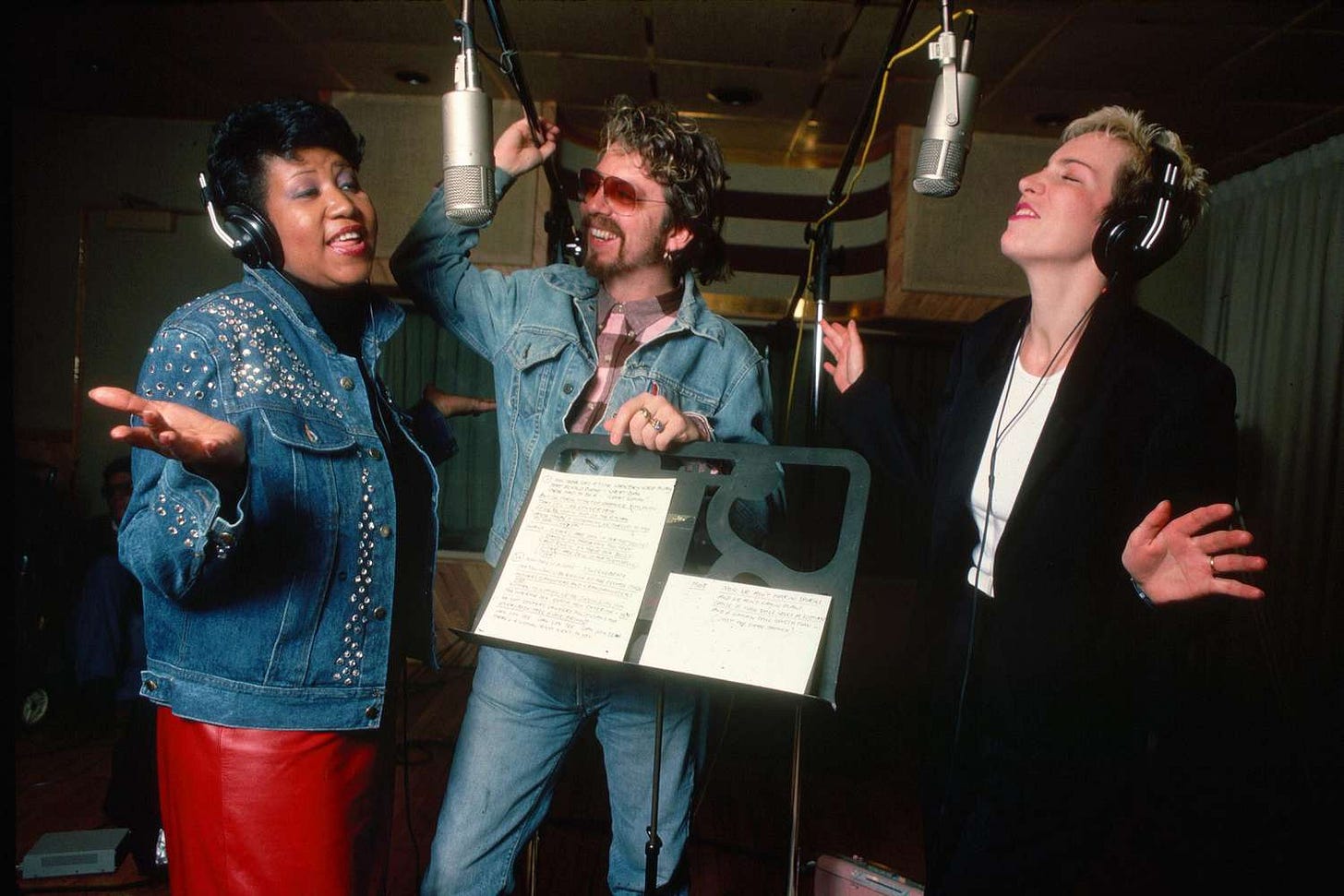

If you’ve never seen photos of Aretha and Annie from the recording session, look at what they’re wearing. Aretha has on a studded denim jacket and red leather skirt. Annie is in a sensible black pantsuit. Unbeknownst to the other, they dressed to impress their counterpart.

“Sisters” became another success for Aretha, with inclusion on both her album and Eurythmics Be Yourself Tonight, released two months earlier at the end of April 1985. And somewhere in a vault, or lost to time, there’s footage of the “Sisters” recording sessions, rehearsals and all, according to David Nathan’s 1985 interview with Aretha. Someone needs to dig that up. It’s also worth noting that backing up Aretha and Annie, aside from David, are members of Tom Petty’s Heartbreakers: Mike Campbell, Benmont Tench, and Stan Lynch.

After “Sisters” opens the second half of the album, the four tracks that follow are largely non-singles, and those that did make it to single or b-side status were just that, secondary. Three more unique Walden productions sandwich between “Sisters” and the closing cut, “Integrity,” a second production from Aretha herself.

“Integrity” is best regarded as something of a triumph for Aretha. It’s only the second time she’s received sole credit as composer and producer on a song, the first being 1979’s painfully underrated “Honey, I Need Your Love.” While especially during this time period, Aretha’s original works in the 80’s tend to get more scrutiny that they deserve, and none of them achieved a fraction of the success her songwriting from 1968-1972 did, “Integrity” should be regarded as one of her best of this decade.

Part of the triumph lies in her ability to retrofit it to the sonic composition of the rest of the album impeccably. It feels right at home alongside Narada and David Stewart’s works, which serves as a testament to her talents as a writer, producer, and arranger. It mirrors “Freeway” with its solo, though she reaches for the legendary Dizzy Gillespie to blow through with his trumpet here. Aretha was a huge jazzhead, and got her secular start playing with the jazz cats in New York clubs. It’s a surprising, yet brilliant idea to bring a jazz legend in for this pop-oriented soul album. That’s how palettes organically expand.

Even the title, “Integrity,” has an 80’s feel to it. And it’s the idyllic perfect offramp for this vehicle that opened on the “Freeway.” And while Narada has a percussionist’s approach to his work which shines through on much of the album, the pianist in Aretha is apparent here. The same can be said for her penchant for a string arrangement, not unlike “Sweet Bitter Love.”

Among the Narada side B tracks, “Push,” her duet with J. Geils Band’s Peter Wolf, which is adorned with a sizzling guitar solo from Carlos Santana, is the best candidate for a single that never was. Earlier this year, Peter released his memoir and wrote extensively about the inception of the record, which he tried to pass on more than once, because he felt that pairing Aretha with himself was “as incongruous a combination as a nightingale harmonizing with an alley cat.”

At the session in Detroit, Aretha arrived in true diva fashion: long Cadillac, bodyguards, mink coat. But when he got to talking with one of the bodyguards and revealed that he knew King Curtis, Aretha’s late, great saxophonist and one-time bandleader, everything shifted.

Peter Wolf saw the woman behind the diva peek through. Aretha lamented Curtis’ tragic 1971 murder, reminisced about Don Covay, who he also knew and wrote “Chain of Fools,” and played an impromptu solo on the piano.

It was only when Narada returned to ask for one more take that Our Lady of Mysterious Sorrows, as Jerry Wexler referred to her, retreated and Aretha the Queen Diva returned. She chided Narada for his request, grabbed her mink and her bodyguards, and exited stage left to her Cadillac. Session over.

The album’s final single, was also released without an accompanying visual. Perhaps three music videos was more than enough this time around, although a visual for this one would’ve been a trip. “Ain’t Nobody Ever Loved You” opens with one of my absolute favorite Aretha ad-libs. Before you hear music, singing, anything, Aretha gets up against that microphone and goes, “Girl, who is that institution over there?!” It’s hysterical, purely Aretha the comedienne, and any mystery around what just happen quickly evaporates as steel drums emerge, and Aretha coos, “come back to the islands with Ree, man” in a faux-Jamaican accent. What is happening?! It’s one of the only Caribbean-flavored songs Aretha ever recorded, although it’s a little more Lionel Richie “All Night Long” than anything else, but it’s a fun record.

Below the surface, there’s something striking about the lyric, “ain’t nobody ever loved you, like I’m gonna love you.” In some ways, it’s the opposite extreme of her first million seller, 1967’s “I Never Loved A Man The Way I Love You.” There, she was so in love like never before that the no-good, lying, cheat of a man had his hooks in her and she couldn’t, and seemingly didn’t want to get them out. Here, she’s the confident, self-assured Queen; her love is definitive and superior to all others. What a mark of maturation and yet at the same time, braggadociousness?

Released on July 9, 1985, Who’s Zoomin’ Who? became a milestone in Aretha’s catalog. It was her first top 20 on the Billboard 200, her highest charting position on the albums chart since 1972’s Young, Gifted and Black. It was also her penultimate top 20 album. Her only other new release to crack the top 20 on the albums chart was her final LP, 2014’s Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics.

It earned Aretha notched her another Grammy, her second of the decade, which was Walden’s first win. It also became her only platinum-certified secular LP. Her only other album to reach that certification was 1972’s crucial gospel LP Amazing Grace, which has been certified 2x platinum.

Though she rarely performed most of the album live, she took the “Freeway Of Love” all the way to the end of the road. It became a staple of her live performances, often the closing number. According to setlist.fm, which compiles setlists (though should be noted, is far from complete), it was her fourth most-performed song of all time. At a moment’s notice, “Freeway” could veer from the secular “love extension” into the spiritual lane. She’d direct the background signers to contort their choruses of “freeway” into a range of gospel charged replacements including “Jesus,” “higher,” and/or “shouting.” When she was really feeling it, closing performances of “Freeway” could span more than 10 minutes. She’d turn the stage into a revival, laying new asphalt with every gospel-charged cry, expanding and contracting the freeway all the way from five lanes down to one as she grinded traffic and tempo to a slow, simmering pace so she could deliver a spiritual testimony. It was a masterwork of live music to see Aretha’s “Freeway” stretch along these varying landscapes.

Who’s Zoomin’ Who? and Aretha’s union with Narada didn’t just mark her musical rebirth; it also established a new formula for her to follow, akin to the ones she’d followed in previous iterations of herself; the last of such formulas that would emerge in her long career. In the early 60’s at Columbia, the formula was largely a mix of originals and interpretations set with a specific producer, aimed at scoring a long sought-after hit. At Atlantic, it was a similar mix, but helmed consistently by Wexler and Co., aimed at continuing the success they saw from the inception of their releases.

Now Aretha had Narada. He became the lynchpin of the two secular albums that followed, in fact, two of the songs that landed on her 1986’s follow-up to Who’s Zoomin’ Who? were recorded during these sessions and held. Their formula got Aretha another Grammy and her first platinum LP, but their next LP would notch another milestone. Though the quantity of their collaborations shrunk after their third collaboration in 1989, he produced at least one track on each of the two albums Aretha released in the 90’s. Their mutual love and respect for one another carried until Aretha’s final days, and Narada even sat in for her on drums during some of her final performances in the mid 2010’s.

In 2014, U.K. label FunkyTownGrooves brought Who’s Zoomin’ Who?’s supplementary material into the digital age for the first time. They reissued the album as a 2CD set, including 16 of the album’s 17 remixes, which have now even found their way to digital/streaming platforms. Just one remix was missing from this comprehensive collection: “Freeway of Love”’s ‘Pink Cadillac Mix’ by Alan 'The Judge' Coulthard, which was issued on 12” pink vinyl in 1985.

40 years on, Who’s Zoomin’ Who? continues to prove impactful. Just last week, RuPaul’s Drag Race’s latest season used, perplexingly, part of “Who’s Zoomin’ Who?”’s acapella mix for the show’s weekly lip-sync challenge. The acapella mix is a must-listen, because it adds nearly 50 seconds of additional vocals, including a few choice ad-libs from Aretha that should’ve been released with the track behind them.

Stream Who’s Zoomin’ Who? below: