Aretha Franklin's 'Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington' Turns 60

Aretha delivers her best work on Columbia Records just weeks after Dinah's death.

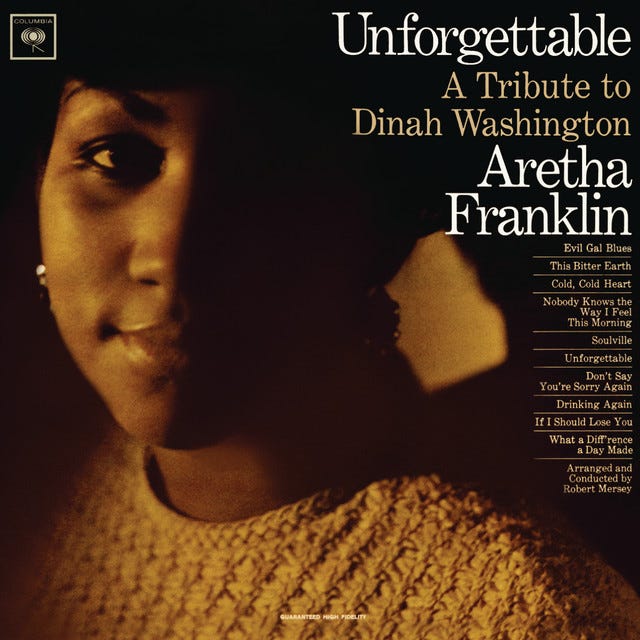

Barely 8 weeks after 39-year-old Dinah Washington’s December 1963 death, 21-year-old Aretha Franklin entered the New York City recording studios of Columbia Records at 799 7th Avenue. Over three days, February 7,8 and 10, 1964, she recorded 10 songs from Dinah’s catalog. Produced, arranged, and conducted by Robert Mersey, Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington was released a dizzying 8 days later on February 18, 1964. Her fifth LP, Unforgettable is often regarded as Aretha’s strongest body of work out of the dozen albums she recorded at Columbia Records between 1960 and 1966, despite being overlooked commercially at the time of its release.

“That girl, has got soul,” Dinah Washington said of Aretha Franklin at a Detroit nightclub in October 1963, 2 months before Dinah’s untimely passing. That’s how the liner notes to Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington open. Aretha revered Dinah, and they’d been acquainted for years. Dinah had been coming around to Aretha’s house since Aretha was just a child, as part of the legendary gatherings hosted by Aretha’s father, Rev. C.L. Franklin. In her autobiography, Aretha remembered watching one evening from her shrouded perch at the top of the stairs as her future husband Ted White carried Dinah out of the house one evening. Aretha wasn’t sure why Dinah was being carried out, but suspected she had gotten “overzealous.”

Quincy Jones recalled Dinah telling him that Aretha was the “next one” when Aretha was just 12 years old. Dinah would know better than most. As Quincy said of Dinah in his autobiography, Q, “Once she put her soulful trademark on a song, she owned it and it was never the same.” That quote could just as easily be about Aretha. Dinah’s masterful capacity as an interpreter is crucial to the artistry of Aretha Franklin. Dinah stretched from jazz to pop to blues to gospel to the moon and back, unlike most others of or before her. Along with inspiration from other crossover acts like Sam Cooke, these genre-defying musicians helped inform Aretha’s ability to not confine herself to one realm of music.

Aretha and Dinah were different artists, with different approaches to their music, and that comes across clear as day on Unforgettable. Aretha’s interpretations of these songs Dinah first put her stamp on are a full-on showcase of the power 21-year-old Aretha possesses, and the capacity she has to master, straddle, and blend genres. She puts more force behind her vocals than Dinah did. Make no mistake, Dinah had tremendous vocal power, but Aretha applies her own power more freely and frequently than Dinah did on her versions of these songs.

At moments, Robert Mersey’s arrangements across Unforgettable evoke a dark, dingy, and smoky club. At others, as the string arrangements glide through the air as they would at the finest of theatres. It shouldn’t be surprising to learn that he dimmed the studio lights to create an “after midnight” feeling. His arrangements draw on all the genres Dinah touched: jazz, blues, pop, R&B, gospel, while adding in flourishes of country, and the soul that Aretha would be crowned queen of just months later in May 1964 at Chicago’s Regal Theater. Many of these arrangements are all uniquely Aretha, and give her a lot of space to stretch out and showcase her voice.

Mersey and Aretha had been working together for more than 2 years. He arranged a few cuts on 1962’s The Electrifying Aretha Franklin, and produced, conducted, and arranged both 1962’s The Tender, The Moving, The Swinging Aretha Franklin and 1963’s Laughing On The Outside. His arrangement of “Skylark” on the latter LP is among Aretha’s greatest recordings. Despite the artistic success of Unforgettable, it would be their last collaboration. Mersey moved on to work with Barbra Stresiand after Aretha, who earned her first number one album and a Grammy for her work with Mersey. The former was something Aretha would never receive, and for the latter she wouldn't even receive a nomination for another three-and-a-half years.

An important piece of history to correct: Sources have said that Aretha had just given birth to her third child, Ted White Jr. in the days (yes, days) leading up to recording the album. However, further research has proven that to be untrue. Though the exact date of Teddy’s birth isn’t known, a February 14, 1963 edition of Jet Magazine (which is mis-dated as 1962 on the cover) features his birth announcement, indicating that he was around 1 year old when Aretha was recording Unforgettable.

According to David Ritz’s ‘Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin,’ Aretha’s husband/manager Ted White wanted to call the album What A Difference A Day Makes. Ruth Bowen, who was both Dinah and Aretha’s agent, was aghast at the audacity behind suggesting that title. It subtly implied that Aretha was the new Queen of the Blues, a sentiment Aretha vehemently pushed back against when the press implied the same. Bowen was relieved when they elected to title it the much more respectful, Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington.

Unforgettable was not just the perfect title for this tribute album, it was also the perfect way to kick off the 10-track LP. Aretha applies her own style to the song, bending and stretching the melody to her every whim and will. She delivers a gorgeous reading of “Unforgettable,” and then stakes her claim to it. While Dinah pleads to be considered unforgettable, Aretha takes a different approach. The song crescendos and her “that’s why”’s charge through with immovable force. Instead, she repeats the final stanzas, emphasizing with vocal immensity the gravity of two people finding one another unforgettable.

There are very few live performances of songs from Unforgettable, but in 1994, Aretha brought the title track out during a few tour stops, including the Westbury Music Fair.

She takes a similar approach to “What A Difference A Day Made” as she does with “Unforgettable.” Aretha opens the song acapella, which becomes a recurring trend in these rearrangements. It directs the focus to her incredible voice. The performance here is just as sublime as “Unforgettable,” and features an equally stunning vocal show-out as she repeats the second verse.

Hank Williams wrote and made “Cold Cold Heart” a country classic in 1951. That same year, Tony Bennett converted the song into a pop/jazz standard, and Dinah recorded a similar version months after Bennett released his. Mersey’s arrangement is unique and distinct, forgoing the pop road followed by Tony, Dinah, and the others, and instead inverts the song back to its country roots while heavily incorporating blues and gospel. The harmonica part creates an intersection of blues and country, while the B3 organ accompaniment gives it gospel flavor. She sheds most of the original melody and instead sings it like a hymn she’s blues-ifying. This is a moment that, despite being largely overlooked, is a stepping stone in the forging of soul music as we know it today. She draws on elements from all these different genres to create something that is fresh and distinct from other things happening at the time.

One of the most significant moments on Unforgettable comes at the very end. “Soulville” is electric in the hands of Dinah. Opening with a call-and-response that recalls Ray Charles’ ‘What I’d Say,” it has a similar sound; an early R&B/soul feel with brass and woodwinds applied in a newer way that was previously utilized in jazz or blues.

There are two things that are crucial to Aretha’s version of “Soulville.” First, it’s the only cut on the album where Aretha accompanies herself on the piano. Her accompaniment is so essential to the arrangement that it even opens the song, scrapping the call-and-response vocals of Dinah’s and instead just leaving Aretha and her piano.

The other thing that’s important is the background vocals. Aretha is responsible for every single vocal on the track. It’s one of the earlier examples of overdubbing, a technique where multiple tracks are recorded on top of one another. It’s ubiquitous in music today, but back then it was neither fully developed nor commonplace. In her autobiography, Aretha recalled how she leaned on the experience of her years spent with James Cleveland as a teenager to elicit the confidence to create her own harmonies and backgrounds. Hearing her take full control arranging and recording the background vocals is stunning. She delivers a masterclass in blending her and harmonizing with her own voice. This triumphant moment foreshadows the tremendous background vocal work she would do in the coming years and decades on many of her biggest hits.

“Evil Gal Blues,” the first song Dinah ever recorded, gets a spirited makeover in Aretha’s hands, all the way down to the lyrics. Leonard Feather, who originally wrote the song when it was “Evil Man Blues,” wrote two new verses special for Aretha. Aretha becomes a self-serving menace with expensive taste thanks to these new lyrics, and spares no bit of soulfulness as she proclaims her wickedness. The incorporation of the B3 organ adds a gospel flair, while the arrangement otherwise leans into a big-band style with hints of blues, especially when the harmonica solo hits. B3 aside, it wouldn’t be out of place on 1969’s big band LP Soul ‘69.

She performed the song on The Steve Allen Show in 1964, blending lyrics from Dinah’s version and hers own:

Aretha dives deeper into the blues on “Nobody Knows The Way I Feel This Morning.” The B3 organ is again a focal point that blends perfectly with the bluesy arrangement. It’s not a far cry from arrangements she’d utilize to gain her biggest hits on Atlantic Records in just a few years. But 21-year-old Aretha is still singing a bit differently than 25-year-old Aretha would. Despite the power, the soul, and brilliance, there’s a piece of her potential that remains untapped. Even at 4:10 when she hits a chill-inducing run (and hinting at what’s to come in upcoming years), that chill is momentary and she seems confined beyond that moment. It could be that she’s not at the piano, anchoring the arrangement herself.

While Aretha matches Dinah’s energy on some songs, on others, they contrast. Dinah is wistful and even a touch passive at moments on “If I Should Lose You,” but Aretha is much more somber, following Mersey’s arrangement. It’s like a smoky theater has gone dark and a single spotlight is hitting Aretha as she ruminates on the prospect and magnitude of the loss. Her voice carries such gravity at the prospect.

Aretha’s take on “Drinking Again” opens with her stripping away Dinah’s opening lines that precede the title and diving right in. The way she bends the “I” packs a serious punch and emphasizes her vocal power. And while Aretha’s struggles with drinking wouldn’t peak for a few years, she sure sings they’d been affecting her, as they had Dinah. Her performance of “Drinking Again” also had a particular impact on another legend in the making: Bette Midler.

Bette Midler has said that the Unforgettable LP, especially Aretha’s performance of “Drinking Again,” shaped her entire way of singing. “It was a real awakening,” Bette said. “It was like I had no idea what music was all about until I heard her sing. It opened up the whole world.” “Drinking Again” would become a standard in Bette’s repertoire, and was included on Bette’s self-titled sophomore album alongside another song Aretha owned, “Skylark.” A friend of mine also sent me bootleg audio he took of Bette singing “This Bitter Earth” live in 1973 with Barry Manilow accompanying her on piano (which has never been publicly heard). Though she makes it her own, Aretha is definitely at the root of her rendition.

Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington was neither the first nor last time that Aretha would give credence to Dinah. She’d already covered Dinah on more than one occasion prior to recording Unforgettable, and would occasionally add to that list in the decades that followed. On her final album, 2014’s Aretha Franklin Sings The Great Diva Classics, she gave a gorgeous reading of Dinah’s “Teach Me Tonight.”

Robert Mersey’s work with Aretha on this project is nothing short of brilliant. As both an arranger and producer, he elicits the finest collection of performances of Aretha’s 6-year-stint at Columbia Records. Though this project didn’t receive the credence it deserved when it was released in 1964, it is widely understood as being among Aretha’s best bodies of work. Her respect and admiration for Dinah Washington shines through clearly as she makes these songs her own.

I was able to track down just one review of Unforgettable, an August 27, 1964 blurb from DownBeat (thank you to James Vale who shared with me his copy of the clipping), who had bestowed upon Aretha the ‘new-star female vocalist award’ in their 1961 international jazz critics poll. Though the reviewer describes feeling “exhausted” after listening to the album and says that “the power and glory of her Gospel message might well be taken in doses smaller than offered here,” the 4-star review considers the work a triumph. “You believe Aretha Franklin,” it says, and calls her “an emotionally moving and truth-rooted talent.” If there’s one thing about Aretha, you always believed her when she sang.

Listen to Unforgettable: A Tribute To Dinah Washington as well as Dinah Washington’s versions of these incredible songs:

Sources

Ritz, David. ‘Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin.’ 2014

Franklin, Aretha & Ritz, David. ‘Aretha: From These Roots.’ 1999

Bego, Mark. ‘The Queen of Soul’. 2001

Bego Mark. ‘Bette Midler: Still Divine.’ 2002.